Last year, we made the decision to develop our philanthropy and build our learning in the hope that we can play a more useful role for the communities we exist to serve.

We were interested in gaining a deeper understanding of Youth Power and Leadership and have spent the last eight months having conversations with, and learning from, many young people, many of whom are leaders in their own right. It has also enabled us to hear from a broad range of experts who have experience of working with young people in education, youth services, criminal justice, the care system, community services, housing and mental health in the UK. In addition to this, we have heard from, and learnt from, researchers, activists and policy makers, and heard about best practice overseas. We would like to offer our thanks to those we have met who have contributed their time, thoughts and ideas so generously, including those young people who have remained anonymous.

Our learning has prompted us to have many conversations about power in itself, questioning what this is and how it can mean different things to different people. Power in itself is complex and multi-faceted. We have heard that the language surrounding power means different things to different young people, and that it is recognised, developed, expressed and utilised in different ways, too.

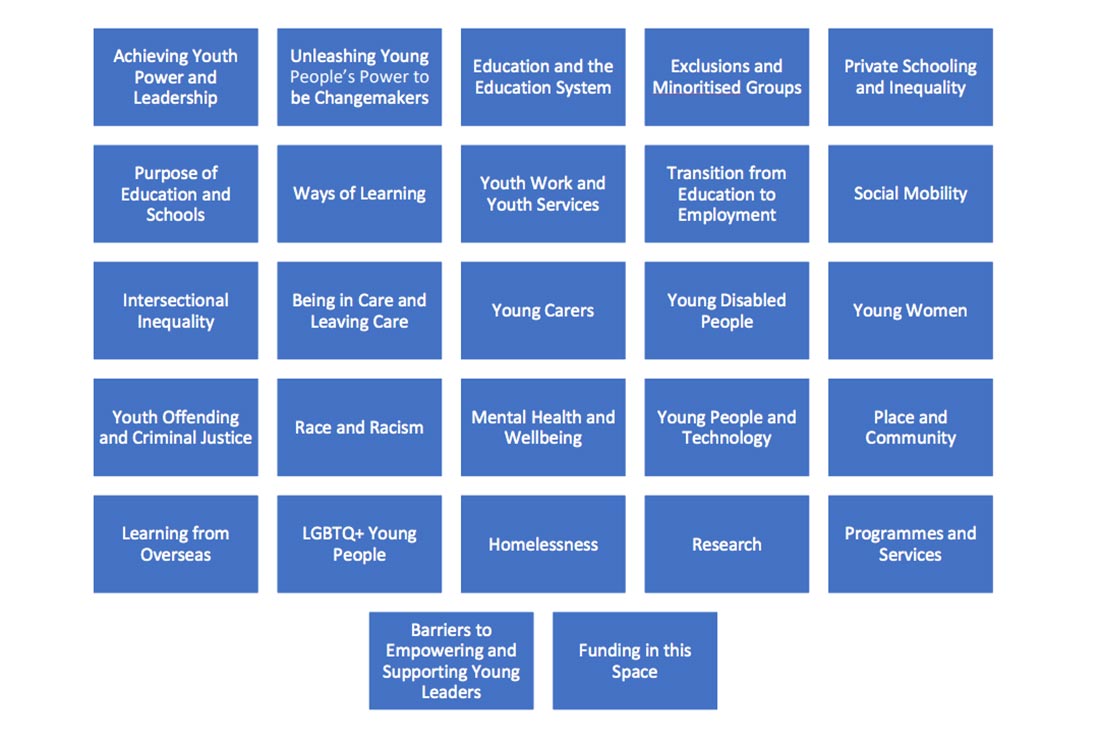

We have summarised our key areas of learning below, and a more comprehensive version can be found within our Emergent Narrative.

Our Key Conclusions

We have seen, heard and felt the passion of many people dedicated to making the world a better place for young people. From our insight, there are six key issue areas that we believe underpin everything that we have heard and learnt. We believe that these issue areas are systemic failures that are preventing young people from developing, recognising and using their power to be leaders.

1. A fundamental lack of youth power throughout society

We have been inspired by the young people we have learnt from and we have been impressed by those who support young people to gain and utilise their power. However, we believe that young people fundamentally lack power within today’s society and that this will impact on today’s generation as well as future generations.

We live in a world where adults are the power holders and decision makers. The majority of these adults are not able or willing to sacrifice their power and share it with young people. Our society aims to protect young people based on their age and shields them from making difficult decisions because they are not seen as having the relevant life or work experience to do this effectively and with confidence. Young people are not given safe spaces in which to hold power and the issues that matter most to them are not acted upon in a way that works for them. Young people below the voting age of 18 are overlooked by politicians and policy makers. Funding for youth power and leadership specifically is restricted, and relevant training and support programmes are not readily available, particularly outside of London.

Whilst there are rare, and often extreme, examples of young leaders within the public eye, such as Greta Thunberg, most young people are not seen as, or celebrated as, experts or leaders. However, just from the young people we have met (and we know there are many, many more!), we are convinced that they have invaluable insight, expertise and wisdom that needs to be better utilised.

2. A strong focus on education and academic achievement

The role of schools in the lives of children and young people, and the way in which experiences within education play a critical role in shaping people’s lives is undeniable. However, we have heard with startling clarity that young people live their lives beyond the school gates. They live within their homes and their communities, both of which have at least an equally critical role in their lives and their future.

We have heard that the education system works for many, and it works particularly well for those that are privileged. But it does not work for everybody. It is not inclusive and the prescriptive approach of the national curriculum prevents the education system meeting the needs of everyone equally.

Those with the greatest level of need in society are those that struggle to fit into the system as it stands, and whilst they may receive invaluable individual support from adults, the system itself does not enable them to reach their full potential. There is an overwhelming focus on school performance based on academic grades that is prioritised over developing love and empathy to cultivate a more emotionally literate generation that understands the importance of wellbeing. Many young people, and particularly those from minoritised groups, leave school without the skills required to flourish within the workplace and society.

We have heard that many people think the solutions to the challenges that young people face should sit within education. However, we have heard with equal passion, that schools, colleges and universities are simply unable to meet these expectations due to pressures within the system and the workforce, and alternative solutions are essential.

Local authority funding cuts have led to the decimation of youth services over the past decade. The provision of safe spaces with trusted adults in which young people can develop socially and emotionally are no longer readily available within local communities. Youth work has struggled to survive in many areas, and, where it has, it is often under-valued and under resourced with a poorly trained workforce. Youth services are disjointed, fragmented and misunderstood and continue to be separate from education. This can be seen at a national level and becomes even more pronounced in smaller towns and cities, and rural areas. It appears to be no coincidence that as youth services have disappeared, there has been a steep increase in youth crime, antisocial behaviour and unemployment. Most people have a poor understanding of the value of youth work and the need for proper training for youth workers, with only those that work within these services, or who have accessed them, seeing their true benefit.

3. Social disconnect and inequality

We have heard that there is a huge gap between the reality of young people’s lives based on who they are and where they live. There is a broad consensus that there is a large social disconnect that exists between those who are privileged and those who are not. The set of circumstances that young people are born into and grow up in can make everyday life either easier or harder.

Those that are privileged usually access a good education that is inclusive of extracurricular activities and programmes that are extremely important in gaining the breadth of experience needed to enter top professional careers. They leave school much better equipped and at a clear advantage over others and are more likely to have a successful career. This is in contrast to those that are the least privileged and face challenges in accessing education and whilst within education. They are unable to access the same range of extracurricular activities and their employment opportunities are limited by their educational achievements. This is a huge barrier that has a direct consequence on their ability to develop experience and skills to get on in life, earn money and become more socially mobile. There are high numbers of young people who are not in training, education or employment and who are not just the hardest to reach, but the easiest to ignore. These are the groups of young people who are minoritised and who face a myriad of intersectional inequalities. For some, it then becomes a much easier option and a closer reality to earn money on the streets.

It is clear that those who are least privileged face the biggest barriers and social disconnect. They include young people of colour, young carers, young disabled people, young people in the criminal justice system and young care leavers. We have heard that these young people are being failed by the system at all levels and are most at risk of mental health issues. They require additional time, energy, efforts and resources to build trusting relationships with people, but are often only able to access time-limited interventions and programmes that do not sufficiently meet their needs.

The young people who sit at the intersection of a number of inequalities hold a complex web of unique needs, and those working with them do not usually have a deep understanding of the complex layering of disadvantage, trauma and internalised lack of self-confidence. You can rarely look at one level of inequality without including others that intersect and layer it, but this is often not considered.

For those young people that are the least privileged, there is a general lack of opportunity and general absence of positive role models where young people can see people like them flourishing in life. This stifles their ability to dream and be who they have the potential to be.

4. Lack of sharing of best practice based on evidence and research

Young people live in a world that is siloed and compartmentalised by the systems that exist in this country. We have been amazed by the numerous innovative and transformational projects and programmes that exist, some of which are led by young people themselves, and some of which have been scaled up and brought to different areas of the country. We have been equally pleased to hear about the evidence and research that underpins best practice, however, we have been surprised to learn that there are significant gaps within research, and that those that are the least privileged are at risk of being the most forgotten when it comes to research.

The infrastructure to share best practice within and across the spaces that young people exist within appears to be lacking, despite people’s best intentions to do this. We have seen a pronounced disconnect with regards to the lack of sharing of best practice and of successful interventions outside of London and other metropolitan areas.

5. A mental health system and criminal justice system that fails young people

Mental health issues amongst young people appear to be increasing, and the reasons for this are complex. We have heard about the many significant struggles that young people face with their mental health needs and that those who are in most need of support are unable to access it when they need it. This becomes even more pronounced when it comes to young people who struggle with their mental health and get into trouble as a result of this. Young people who are troubled and are also in trouble face additional mental health challenges when they are in prison, on remand or on probation. Despite a high proportion of these young people experiencing mental health issues, this is rarely addressed, and when it is addressed it is at a superficial level. This is particularly acute when we look through the lens of race, with young black men being disproportionately represented in both the criminal justice system and the mental health system. We have heard that the criminal justice system systemically fails to hear the calls for help from so many who are desperately in need, including young black and brown people experiencing mental ill health who, as a result, often leave the system with more deeply entrenched mental health issues.

6. Inequalities in access to power, influence and funding

There is a general lack of understanding of power – what this is, how it is built and how it can be shared. Young people are not educated about power and are, therefore, unable to build it, articulate and utilise it. Young people do not see themselves as powerful within their community and do not understand how change happens within their locality. Many young people live in households that do not have the luxury of understanding and talking about politics on a regular basis, unless of course they come from a more privileged background where they access a deeper education and are already in a more powerful position based on their family and school networks.

Programmes and interventions that build young people’s understanding of power and their skills and confidence to utilise this are rarely funded and are few and far between. The platforms to utilise this are even fewer, and those who do manage to develop and utilise their power, often do so in isolation and may receive unwarranted attention and criticism for doing so. These young people are going against the grain in a society that does not value young people equally to adults, and this in itself can cause distress at a time when we know it is difficult to access mental health support.

If you would like a copy of the full report or this summary please click on the links below.

Report by The Ellis Campbell Foundation